Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Design By Nature: Cellulose and Sex

Ground Cover and the Boundary Layer

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

The Biggest Bread I Ever Baked

Friday, February 17, 2012

Aesthetics as a Diversity Strategy

Bad Planning

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Plant Clones

Plants learned to clone themselves hundreds of millions of years ago and they continue to do so today. Plants spread by asexual (vegetative) reproduction in addition to sexual reproduction.

From a design perspective, we can utilize plant clones to build effective garden spaces, do land reclamation, and grow certain important food crops.

Plant clones can also be harmful, such as when they clog waterways.

We find plant clones in so many settings. Large plants, small plants, land plants, aquatic plants. Underground and above-ground growth. Leaves that clone, stems that clone, roots that clone. And some organisms that look like plants (like Cladonia boryi below), but which are not related to plants.

Enjoy these photos and please click on each one for more details.

Monday, February 13, 2012

Compost Tea

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Mmmmm Hyacinths

Thursday, February 9, 2012

Plants and Transportation

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

Coral Reef Ecology and Human Impacts

Monday, February 6, 2012

Farming in the Mall?

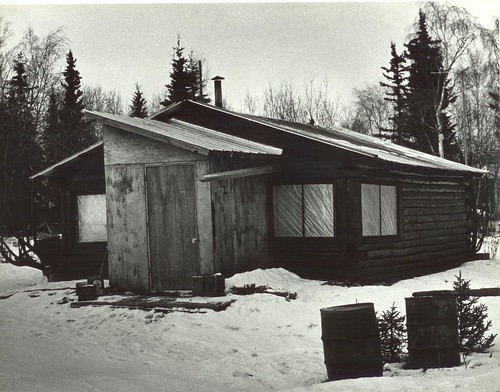

Long ago and far away when we lived in Alaska, there was a commercial greenhouse in town. This was the tiny city of McGrath, way off the grid, an outpost accessible only by dogsled or plane. The Native Corporation, flush with funds from the sale of oil and gas rights, decided to build the greenhouse in town to provide people with fresh veggies and of course, to make money. Here you can see the greenhouse in back of the local tavern, which was ever the bigger money maker. See the moose antlers over the door?