The short answer is, it depends what plant it is. The flowering plants like magnolias don't depend on their flowers to survive. Reproduction, normally the role of flowers, is obviously not essential in our urban garden environments.

But the leaves are another story. Have you ever noticed that on most of the trees, it's the flowers that come first and later the leaves? Plants in the temperate and cool zone have evolved so that the leaves come out of dormancy last. And there's a reason for this. A late frost will kill off young leaves, depriving the tree of nutrients and potentially killing it.

So let's look at the question a little closer. Excluding the flowers, which we've already callously determined as unnecessary, what about the leaves? Again, it depends on the species. Most of the shrubs and trees I've looked at still have their leaves tightly packed in buds. They may not have even begun the process of breaking dormancy. But in case they have, two things might still protect them.

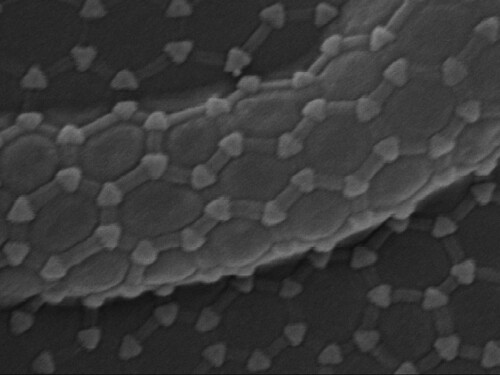

First, structural anatomy. If you look carefully at most angiosperms (flowering plants) you will see that in addition to the main bud, which breaks dormancy first, there is at least one other bud held back in reserve. The beech leaf below is a perfect example.

...or this birch.

Many layers of vegetative covering also protect the young buds. They are slow to lose these layers.

A more complicated and perhaps less well understood protective phenomenon is the suite of metabolic and chemical conditions each plant has evolved into. Buds sheathed in a waxy coating are one example. They are full of anti-freeze and surrounded by anti-freeze. And they are well protected until the cascade of dormancy-breaking reactions starts.

So even though the weather has unpredictably swung back from July to March, I am pretty certain that thanks to millions of years of experience with this sort of thing, the plants have it in the bag.